WHEN, in 1980, Faiz Ahmed Faiz wrote a preface to “Shaam ka Pehla Taara” he hailed Zehra Nigah’s crucial turn towards finding her own true voice after an initial period where she had adhered more strictly to classical form and classical content. This experiment in na-khalis (the impure) marked a climb in her poetry to a “higher plain” and it set her up nicely for distinction in times to come.

Faiz’s advice to Nigah came at the right moment. By then, of course, a few good traditions had already been absorbed and in the subsequent years the mixture of the old and the new has worked in her favour. Three decades later, her appeal lies in the ability to illustrate new scenes with the undaunted patience of a poet well-trained in the basics.

The classical influence is very visible in Zehra Nigah’s lines, even if more in tone than form. The few references to Mir bring out her bias for a not-so-loud but simmering conversation with the people out there. Hers is seething anger which, rather than coming out as a cry of anguish, has progressively taken a motherly hue. She does at one place rather caustically observe, “Bacha phir aakhir bachcha hai” while mostly she is able to communicate without sounding too offensive to many.

This maturing may not be evidenced in her latter-day sequel to one of her most well-known poems, “Shaam ka Pehla Taara”. The upwardly individual in the original “Taara…” appears to have been transformed into a disappointed, lonely soul with an empty gaze, but the poetess who is visible on other pages of the book has been much more productive and inspiring than Zehra Nigah herself gives her credit for.

There is unavoidable emphasis on linking Nigah’s work to the feminine tradition of chronicling human sufferings. But that has been no hurdle in her growing appeal in recent times. Turmoil entails a greater sense of sharing, of pains and hopes, between individuals. It could be that ‘our’ current state has obliterated old demarcations across gender because surely, now there is greater acknowledgement of a sharing across-the-board. The ‘universal’ appreciation of her poems such as “Suna Hai”, one of the most quoted ones of late, is a tribute to her ability to represent the feelings of not just one section but a whole lot of people.

The connoisseurs may sometimes be found craving a certain kind of lyricism in her work and there might be a few of the poems that would appear to some old-school critics as too journalistic and too sudden in nature. This impression may be more peculiar to her readers; her own recitals of her poetry are nuanced, smooth presentations creating a long, uninterrupted melodious spell of their own.

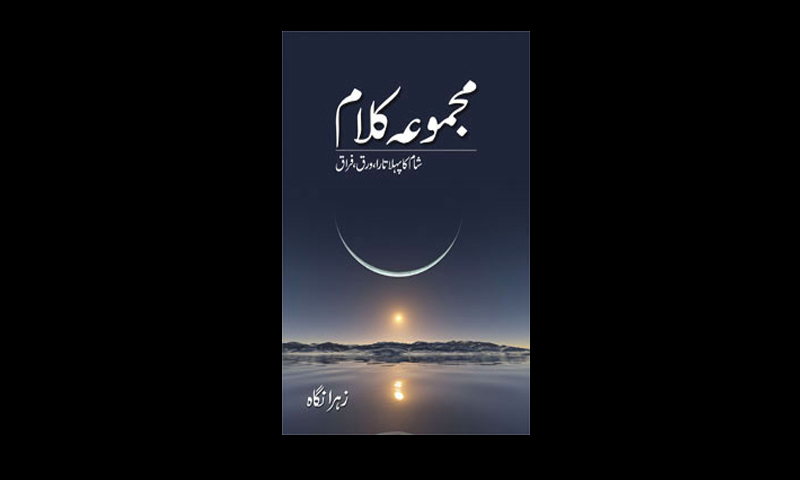

The collection of Zehra Nigah’s poetry, simply titled Majmua-i-Kalam, is a somewhat thin volume for someone who has been active for so many years. It includes what three giants — Intizar Hussain, Ahmed Nadeem Qasmi and Faiz — thought of her literary progress at various points in time. The coming together of the trio in itself may be a significant clue to Zehra Nigah’s own creative inclinations: Intizar Hussain, the storyteller, Faiz, the poet, and Qasmi, who can always have his fans divided over the question of whether he was a better poet or storyteller. The three of them come together to introduce someone who chooses verse to tell a variety of stories.

Zehra Nigah lets her message sink in softly and doesn’t appear to be rushed or overtly angry even when she is pleading with the Almighty to restore the law of the jungle to her city. Many of the titles that she gives to her poems betray the urges of a storyteller in her: “Aik Gurya ki Dastaan”, “Kahani Gul Badshah Ki”, “Kahani Gul Zamina Ki”, “Qissa Aik Hakim ki Zindagi aur Maut ka”, “Aik Kahani, Bari Purani”, “Aik Sachchi Aman ki Kahani”, are all poems which may qualify as brief short stories. And somewhere in the collection, when she meets Scheherazade in a London café, it makes the reader wonder if this is the quintessential storyteller who the poetess wants to model herself on.

A woman working through the long night and ultimately bringing about change through her persistent resistance, that’s an example which would appear to go well with Zehrah Nigah’s own supple but relentless narrative. But, unlike Scheherazade’s penchant — or actually her need — for leaving the story midway through in order to ensure that she lives to tell it another night, when Zehra Nigah decides to relate a tale she wants to relate it as completely as possible.

Thus when she decides to take notice of Dildar Begum, she is quite eager to provide a brief biographical sketch of the woman who now lies buried in her enclosure, respectfully veiled from her lifetime tormentors. She adopts Dildar Begum from the moment she is born and nurses her through the tumult right up to her grave to have the desired effect on the reader. A few pages later, ‘Virsa’ finds the poetess taking account of what she had been born into and what she is leaving behind, with her expression drenched in the right amount of nostalgia for maximum results.

Biographical sketching instead of a focus on one particular incident enriches the poems in Majmua-i-Kalaam and gives the work its distinctive flavour and these seem to come naturally to their creator. To explain why she has not written for a while, Nigah makes it a point to inform everyone around of her personal pains.

The dastaans and the kahanis and the qissas in Majmua-i-Kalaam are detailed stories, remarkably so because usually these are not long poems. The longest of them perhaps is the one which finds a people creating a giant to mind their borders and then being overrun and overwhelmed by this monster.

Woh deo aaj bhi iss shehr pay musallat hai … Woh sarhadon pay nahin bastiyon main rehta hai (That giant is still imposed on this city He lives not on the border but in settlements)

Titled “Khud-sakhta Deo” (Self-created Giant), this poem brings a relatively louder protest out of Zehra Nigah. Here, her landscape expands to include the fields which have been rid of their grain and the rivers and the fruit that have been swallowed. There may be a few other such diversions and at one point, she allows herself the more standard “kaisay kaisay sahab-i-sarwat biknay ko tayyar huway” and the more obvious “Masheenon say nikalti golian aankhen nahin rakhteen’. It does not, however, take her long to return to her groove and take her customary position as a restrained commentator on affairs in this troubled homeland of ours.

The reviewer is Dawn’s resident editor in Lahore

Majmua-i-Kalaam Shaam ka Pehla Taara, Warq, Firaq By Zehra Nigah Sang-i-Meel Publications, Lahore ISBN 978-969-35-2506-9 280pp.

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.