6 ways efficient architecture can help Karachi deal with heatwaves

Summers in Karachi can be extremely trying. In 2015 a deadly heatwave claimed around 1,500 lives in the metropolis. Earlier this year, seeming to recognise the climate change threat, the Sindh government chalked out a contingency plan for another possible heatwave. Heatstroke centres were set up in Karachi in April as the city sizzled at 40.5 degrees Celsius.

These temporary and precautionary measures however can only go so far.

Long-term solutions are clearly the need of the hour. We wondered, can well conceived architecture provide said solutions?

Short answer: Yes, but there are no quick fixes.

“We cannot possibly cover the entire city with a giant heatproof, reflective tarpaulin and hide away from the heat,” says architect Zain Mustafa.

So what can be done? Here’s what some architects, environmentalists and urban planners propose.

1. Introduce green spaces

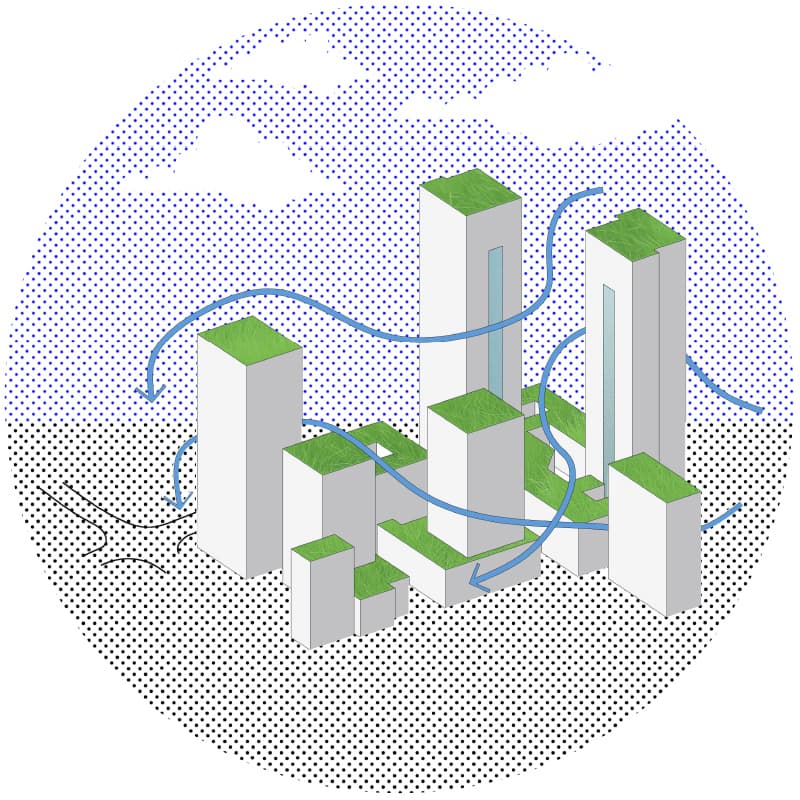

Town planner and environmentalist Farhan Anwer observes that as one moves out of Karachi, even if the temperature is the same as it was in the city, it does not seem as bad. This, he explains, is because there are fewer obstructions outside the city, which means breeze can flow freely.

Buildings in metros like Karachi create a hindrance in airflow, absorbing and retaining heat. They continue to release this heat throughout the day; while vehicles air conditions, exhausts etc. also contribute to a rise in the existing temperature.

Yet, instead of making Karachi better equipped to handle this heat, we are adding to the problem by removing a large amount of trees and ground cover for more construction.

The urban fabric of the city needs green spaces that reduce temperatures, Anwer stresses.

Architect Arif Belguami says that because there is such a lack of “green island spaces” in the city, sometimes in the middle of the road one can see people sitting under the shade of a lonely tree. “There is a humongous need for parks that is unfulfilled,” Belguami says. But since space constraints keep us from building big enough parks, a larger number of green pockets may help curb the problem.

It should be a law to replace the trees cut down due to a new development, Mustafa adds.

2. Plant the right trees

Mustafa suggests taking “a double-barrel approach” where citizens and the government authorities collaborate and plant trees. Covering the city with trees, as a process would take at least half a decade to reach fruition, but it is essential for our city to prosper.

But not all trees are created equal. There are some which actually end up doing more harm than good. We are currently stuck in the past, trying to replicate concepts from Europe or America, rather we need to look at our own regional climate and come up with a solution keeping in mind the indigenous environment.

Horticultural expert Salman Khan points out that planting more than 15-20% of the same species is not ideal, as in case of an outbreak of disease the entire species gets affected.

The last flora fauna documentation was conducted in 1967; this means there is no proper guideline of the types of plantation in the city. But Khan provides some insight saying that we need to move away from planting imported species like conocarpus and eucalyptus, which further degrade the environment by lowering the water table and causing pollen grain allergies. Instead, indigenous species like neem, peepal, barna, gul mohar and acasia should be planted.

Even a massive project like Bagh Ibne Qasim, the city’s largest park covering a total of 130 acres and the most prevalent plantation, comprises of the conocarpus. This is not an indigenous plant according to the Pakistan Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (PCSIR).

Moreover, Khan says that in newly developing areas like DHA phase 8, it becomes impossible to plant trees in the centre median due to the services and drainage that are placed beneath as a conscious design guideline. Hence, only water requiring shrubs can thrive which is a huge waste of our already scarce water resource and does not really benefit the environment.

3. Get our roads and transport systems in order

Khan points out that inferior metropolitan infrastructure contributed towards the high death toll in the 2015 heatwave. Many causalities occurred on way to the emergency centres. We need improved road management and better ambulance services he says.

Architect Azmat Rahim further talks about how cars impact our environment. He stresses that urban housing developments should be planned in a way that we do not need to rely on cars to accomplish simple tasks, instead we should be able to walk or ride a bicycle for our daily commute.

He adds that there should be a car rationing system to curb emissions. He cites Delhi as an example where such a system has been successful.

4. Go old-school

Rahim believes that we should go back to old design practices that considered our climate, region and had proper ventilation. Havelis, verandas, wind catchers and even old-school insulation techniques can all be implemented today.

Mustafa also stresses the fact that we should learn from senior architects like Arif Hasan, Kamil Khan Mumtaz, Najeeb Omer and Shahid Khan who “build looking at the bigger picture”. We need to gather all our resources and look towards our experts and academics, he says.

5. Revisit the bylaws

Rahim stresses the need for seminars, conferences and meetings to pass new bylaws. Bylaws should include landscaping; there should be a mandatory number of trees planted according to size of the site and the type of trees allowed should be included. These bylaws should also extend to the use of materials for construction. They should also monitor the allowable percentages of glass on the facade.

He believes that the media can also play a role by raising public awareness about these matters.

6. Use colours that do not absorb and radiate heat

Anwer suggests environmentally responsible gestures, even as subtle as changing the colour of concrete cover in the city to one that does not absorb heat, can make a difference.

Reporting and illustrations by: Shahzaib Arif Shaikh, Mishaal Rahim, Marium Rehman and Abdul Fateh Saif

Header photo: AFP