Population census 2017: Why this extensive exercise will be defective

Why this extensive exercise will be defective

Delayed by nine years, the national population census is to begin on March 15 with a house listing operation. Unfortunately, even with 200,000 army personnel and 91,000 civilian enumerators at its disposal, the exercise, which will cost the exchequer over Rs14 billion, is likely to be seriously flawed. In fact, if it is allowed to proceed in the way that the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS) has designed it, this exercise will be looked upon as the biggest disservice to the nation.

The main reason for this is that, unlike the 1998 census, this time enumerators will concentrate on conducting a nationwide headcount — involving the collection of basic demographics such as gender, age, marital status, religion — without completing Form 2A [see next tab]. This implies that significant data on disabilities, internal migration, mortality, fertility and other social indicators will be left out.

It is not clear why the PBS — tasked with planning and conducting the exercise — has decided to omit the collection of such vital information. In fact, with the army available for the 70-day exercise and enumerators having more time to collect house-to-house data, additional questions could easily be asked — even though there are drawbacks to having a prolonged census exercise as discussed later. Usually, two weeks are allotted for the exercise; but in the current case, the census will end on May 31.

But the PBS remains unmoved. “We don’t have the time to use this form [Form 2A] for the current exercise. This census is a snapshot of the population on the day [March 18]. After March 18, we won’t count those who die or are born. Enumerators will note an aggregate number [door-to-door]. The additional data collected through Form 2A will be done in the third or fourth quarter of the year, if we are given permission,” says Asif Bajwa, chief statistician at PBS.

Not more than a headcount

Observers would be justified in asking that if this is merely a headcount (despite the enormous allocations — army, civilian and financial) wouldn’t it defeat the purpose of holding a census? Wouldn’t it just be a waste of precious national resources? Political disinterest and poor planning on the part of PBS are apparent here. For instance, since local schoolteachers will be trained to double as enumerators it would make sense for them to collect relevant and complete census data at one time rather than disrupt their regular teaching commitments at the end of the year yet again.

Complete census information is are vital to addressing a variety of social challenges, such as Pakistan’s education emergency, increasing malnutrition and stunting, water shortages and lack of adequate health facilities. “Population censuses are used for constitutional functions such as inter-provincial resource allocation and the distribution of national assembly seats. Census also provides a sampling frame for representative surveys. If a country is unable to conduct a credible census it is usually a sign that there are unresolved political issues which are generally more of a problem for development than not having census data,” explains social scientist Haris Gazdar.

The question is whether this government understands the importance of population data collected in a transparent manner, and with the use of technology for reliability and accuracy.

It also appears that professional demographers privy to pre-census preparations are concerned about the exercise about to hit the road. At the centre of it all, PBS insiders requesting anonymity say the government is devoid of commitment and is merely fulfilling the Supreme Court’s directive instructing the bureau to get on with the exercise because the census is a constitutional obligation. According to them, the PBS, in control of planning, preparation and the rolling out of the exercise, was determined to ensure that the army lends credibility to the operation so that all stakeholders accept the results. The previous army chief had refused to lend more than 42,500 troops, hence the delay in holding the census. Meanwhile, there has been no effort to conduct pre-census preparatory operations which would have meant a thorough pilot census.

The question is whether this government understands the importance of population data collected in a transparent manner, and with the use of technology for reliability and accuracy. Demographer Mehtab Karim, who recently joined the PBS’s sub-committee on the census, says that “data [such as fertility data] collected must serve as the basis to the map-changing patterns of family or household formation…. It must be used for population projections, which, in turn could determine the scale of future health, education and other services.” Because population data comprises components integral to fertility, mortality and migrations trends, experts say this kind of information helps map growth rates more accurately.

For his part, Mr Bajwa holds the Council of Common Interests (the inter-provincial body chaired by the prime minister and represented by the four provincial chief ministers) responsible for the decision of omitting additional questions. “With 55 million forms printed at the cost of $3m, I can’t change them at the last minute to insert additional questions, can I?” he says. However, insiders at PBS say that the bureau itself recommended to the CCI that Form 2A should not be part of the exercise.

UNFPA recommendations

One PBS governing council member cites additional reasons that could turn this into a defective exercise. He refers to technical recommendations sent by the United Nations Population Fund to PBS on Dec 14, 2016. In a letter addressed to Mr Bajwa, the UNFPA strongly recommends certain pre-and post-census mechanisms to ensure quality. They include a pre-enumeration pilot census to examine the mobilisation and preparation of field staff; the use of maps; the need for safe transportation of forms from field sites to Islamabad; and up-to-date software for technical data processing. PBS spokesperson Habibullah Khattak admits that there has been no pilot census. Clearly, a pilot would ensure that the entire process runs smoothly from start to finish.

UNFPA also recommends a plan for a potential two-day extension in each enumeration area, and monitoring progress after seven days, if more time is required. Further, the UNFPA letter (available with Dawn) also refers to the need for a census master plan “to dispel confusion over de jure (when persons are counted at their place of residence) versus de facto enumeration (when persons are counted on the day where they are found) and clarify exactly who is to be counted within the household.” In 1998, both approaches were used during enumeration but the data counted was of those persons present at the time and on the day. Further, it notes that provincial and local governments need to be fully aware about the exercise, so that they can prepare to utilise the results for planning policies and programmes.

Everyone counts: why accuracy and clarity matter

If a country is unable to conduct a proper census, there will be no credible basis for planning its development programmes, Mr Karim explains. Having monitored census exercises for the UN, he cites the 1981 census as being closest to the most accurate. For instance, during the post-enumeration survey, only 3pc of the population was reported as missed, whereas in 1972, the growth rate in certain districts of Sindh and Balochistan was overrepresented. Meanwhile, four to five basic questions were asked during the haphazard 1971 census that was conducted under pressure. “It was unlike in 1981 when the quality and content [of questions] and the accuracy of coverage were near perfect.”

The advantage of a rapid census exercise is that it reduces the chances of error. Stretched over three months, the exercise might fail to capture accurate population data. Dr Nizamuddin, a member of the PBS governing council, agrees that a brisk census exercise is required in a tight framework — usually 15 days to be followed by a post-enumeration survey to check the population percentage missed. Then, without state-of-the-art technology for tabulation and trained enumerators with expertise in interviewing, and with little attempt to bolster the capacity of PBS and its counterparts in the provinces to collect, archive, organise, analyse and disseminate census data, the exercise would be futile and a waste of resources, say demographers. “Census data must be used for fiscal and assembly seat allocation between the provinces. That is the law. Development planning in Pakistan is not always done to very high scientific standards. The issue is not so much the supply side that is the quality of census data as it is the demand side that is the quality of development planning,” Mr Gazdar says.

As in 1998, Pakistanis studying or working abroad, away from their places of residence (in this case for over six months), will not be counted as part of the legitimate population. This has sparked concerns of undercounting as government statistics show that 8m Pakistanis live abroad. The other challenge is documenting Pakistanis without CNICs and non-Pakistanis. The census field operation plan booklet states that all aliens will be counted as non-Pakistanis. Afghan refugees in notified refugee camps will not be enumerated but those who live within residential areas with ordinary populations will be counted.

It remains unclear why PBS has taken the decision to collect incomplete census data in addition to not adhering to certain mandatory procedures pre-and post-enumeration. At the expense of the provinces, spending billions of rupees, the PBS is set to deliver a half-baked outcome that will not paint a candid state of the nation.

Header illustrator by Reem Khurshid

Read more about what the census will not be documenting in the next tab.

What the census will not be documenting

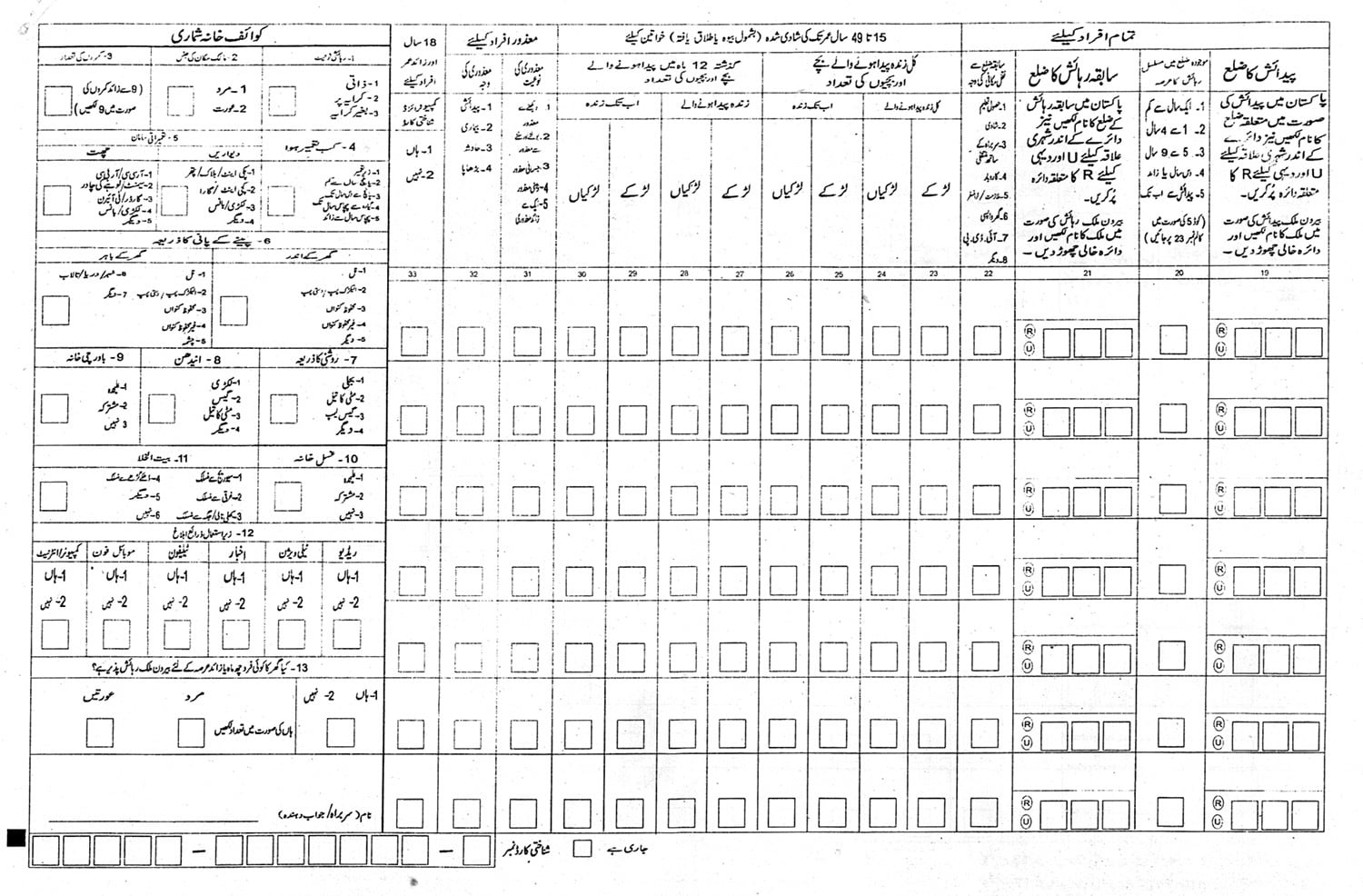

During the national census, 13 questions pertaining to demographic details per household will be asked as specified in Form 2. Enumerators going door-to-door will collect data such as the name of the head of the family, the relationship of other persons living in the household to the head of the family, gender, age, marital status, religion, mother tongue, nationality, literacy, occupation during the last 12 months, CNIC (for those above the age of 18), nature of residence (owned, rented, without rent) etc. Recently, debate in Sindh, ensued over the exclusion of Gujrati - it is one of the languages not listed in this form. Moreover, the listing of only six religions, omitting some, was taken up by members of the Sindh government.

Form 2A, with an additional twenty questions, will not be used during the census. Therefore, additional and detailed information such as the district of birth for all individuals, the duration of residence at present, previous district of residence (whether urban or rural), details pertaining to education, fertility (for women between 15 to 49 years, data collected on total live births), migration, disabilities, etc will not be collected. Information collected for this questionnaire point to significant socio-economic statistics that are imperative for meaningful policymaking. This omission, therefore, implies the exercise is being conducted in a hurried manner without giving thought to the purpose of a national census and its impact on the broader health of a nation. — Razeshta Sethna

Next tab: We explore the extent of the army's involvement.

Army involvement goes beyond security cover

For the upcoming population census, it has been reported that the army will also conduct a separate headcount and collate data on a specially designed forms alongside civilian enumerators. This has raised questions regarding the role of the army. For a moment, rewind to last year, when the Supreme Court had asked the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS) why the army was required to conduct a national census. On its part, PBS cited security conditions as the reason. While the former army chief was reluctant to lend a huge number of troops, he had agreed to 42,500 due to their paucity. But the incumbent, General Bajwa has finally agreed to lend 200,000 while the PBS had initially demanded much more. However, conducting a parallel headcount, after which data collected will be stored with the army, is another matter.

Given that enumerators are local officials — schoolteachers or patwaris — Asim Bajwa, the chief statistician at PBS, believes that “they need someone to monitor the exercise so that the enumerator is safeguarded from local pressure.” He explains the role of the army as “keeping a countercheck on the civilian side because we can’t be trusted with a headcount.” However, PBS staffers on condition of anonymity say that they recommended as far back as 2015 that the military was not an essential cog in this process, unless of course required to accompany enumerators in volatile areas of Fata, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and Balochistan.

One PBS governing council member (on condition of anonymity) confirms that data collected by the army will not be processed alongside Form 2 (used by enumerators) at the post-enumeration stage. Information collected by army persons will include the name of the head of the household and number of Pakistanis and foreigners residing in a particular household. He goes on to say that “the civilian dispensation is simply interested in doing a headcount; the army is being brought on board to lend credibility and they are doing their own headcount through an independent form printed by PBS for that purpose. If the results are not reliable and not comparable to other data collected, then the onus lies with the PBS.” Separate forms to the tune of 55 million to be completed by the army will be stored with the military when the exercise has finished and in the case of identification of any differences they will cross check results with the forms completed by enumerators says PBS spokesperson, Habibullah Khattak. How that will happen and at what stage in the census exercise is unclear at the moment. Some PBS insiders do not agree with Mr Khattak, who claims that conducting the census under the supervision of ‘neutral umpires’ will remove major anomalies.

Instead of investing in better trained enumerators and supervisory staff able to form a meaningful pool for future sample surveys and/or bussing-in enumerators from other districts, it appears the only solution that PBS managers could come up with was badgering the military to supervise the census, says Nuzhat Ahmed, former director of the Applied Economics Research Centre. This has meant that over 50pc of the cost has been budgeted for payments to the army — cost shared by the provinces for what appears to be duplicating headcount data. — RS and FZ

To learn about the economics of the census, click the next tab.

The economics of the census

Holding a population and housing census is an expensive exercise. However, a comprehensive census promotes national cohesion and saves enormous amounts of resources through accurate planning and cutting wastage. That said aborted censuses are a waste of resources. In the recent past, the 2011 census was suspended after a 3-day house listing operation. While this aborted exercise cost the nation close to Rs4 billion, no penal action was taken against officials responsible for the fiasco, if any. Verbal blame was levied against political parties and some unnamed vested interests. Then, the census was delayed for another five years, until the Supreme Court took it upon itself to direct the federal government to hold a census.

On the basis of a summary from the statistics division of the Ministry of Finance, the Council of Common Interests approved a budget of Rs14.2bn for the census to be drawn from provincial financial shares. At the time, the finance ministry envisaged sharing of the budgeted amount to be equally divided between the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS) and the army for providing 380,000 troops for the exercise.

In the recent past, the 2011 census was suspended after a 3-day house listing operation. While this aborted exercise cost the nation close to Rs4 billion, no penal action was taken against officials responsible for the fiasco, if any.

The Rs7bn earmarked for PBS (population wing) were spread across four quarters. An amount of Rs2bn was released initially. Most of that money went into the purchase of vehicles, machine and equipment. Once the exercise became imminent in the face of SC pressure, another Rs2bn was released by the Ministry of Finance. The remaining Rs3bn has also been released last month. Sources within PBS allege that most vehicles, machine, equipment and refurbished offices remained in the use of officials with the Federal Bureau of Statistics wing that dominates the Bureau and that they faced stiff resistance over the sharing of resources meant explicitly for the census.

In contrast, the 2011 census in India is estimated to have cost 22bn Indian rupees or $350 million. This was the 15th census conducted in India and the 7th after Independence while, in comparison, Pakistan has conducted five national censuses. On another note, while PBS has reduced number of questions for the upcoming census in Pakistan next month, from 33 to 13, the Indian census form required every citizen to respond to 29 questions. — Fahim Zaman