Assessing India's water threat

Blood and water can’t flow together,” declared a belligerent Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi on September 26, 2016 in the wake of 19 Indian soldiers dying in a militant attack on Uri military base, just inside Indian-administered Kashmir. Holding Pakistan responsible for the violence, Modi promised to unshackle India’s policy of “restraint” — implying that India was now going to hurt Pakistan by choking its water supply.

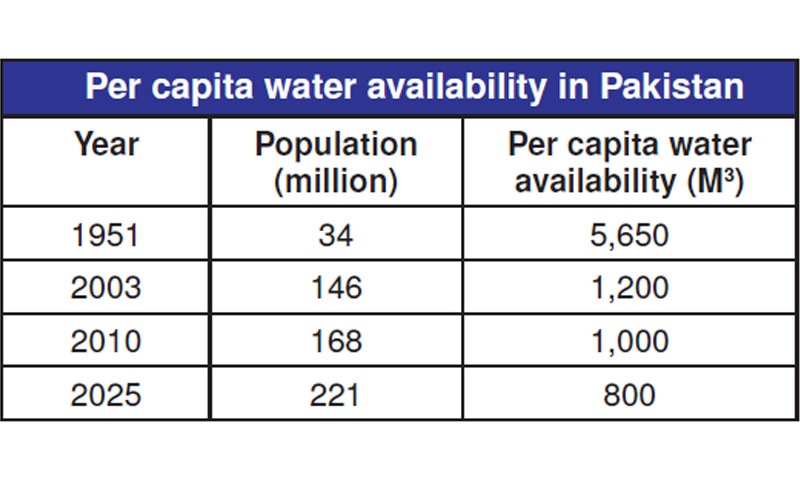

For the people of Pakistan, a nation dependent upon agriculture for its survival, the Indus rivers are their lifeline. As it is, Pakistan is ranked second, after China, in the Water Shortage Index, highlighting the vulnerability of the Pakistani population to frequent water shortages. Modi’s proclamation generated lots of nationalistic hyperbole in the two nuclear-armed twins but also inflicted some damage: many on this side of the border are perturbed about Modi making good on his threat and stopping water supply to Pakistan.

Can Modi turn the taps off immediately?

Can Modi turn off the taps and choke Pakistan’s rivers?

Not quite.

The Indus Waters Treaty of 1960, which governs water sharing arrangements between India and Pakistan, outlines a framework for how either country can exploit water potential and how they can’t. While the Indus Waters Treaty is upheld, India cannot turn the taps off — in fact, it does not have the capacity at the moment to do so either — but it can definitely delay the release of water flows. And historically, India hasn’t been averse to using this tactic when relations with Pakistan turn sour. This time has been no different.

Also read: International Law on Water Rights

In a story printed in the October 12 edition of Dawn, irrigation department officials warned of a record reduction of water levels at Head Marala in the Chenab. The fear is that water shortage in the river and two of its canals, Marala-Ravi Link Canal and Upper Chenab Canal, can adversely affect the sowing of crops particularly in Sialkot, Gujrat, Gujranwala and Sheikhupura districts. The situation has worsened at the time of this report going into print.

The cultivation cycle in the subcontinent is divided into two seasons: khareef (monsoon) and rabi (winter). Khareef sowing starts in July or even June while the sowing of rabi crops begins in September and October, depending upon glacial melts and the amount of rains. The water flows in the Indus system varies exponentially in different months. Up to 90 per cent of flows can be accounted for during July to September.

For rabi crops such as wheat, pulses, onions, tomatoes and potatoes, timing is crucial. With October at an end, the record reduction of Chenab water flows can translate into delayed rabi sowing, which in turn will adversely impact produce for local consumption in the coming season and lead to price inflation.

In practical terms, consider this: tomatoes are being sold in the market at 25 rupees per kilo today; expect this price to rise manifold in the coming year. This is besides the food and income insecurity that thousands of growers in Punjab and Sindh will be pushed into.

A crisis is certainly brewing.

Beyond hyperbole and nationalistic fervour, the two South Asian giants need to be at the negotiating table. Normally a dispute like the one reported by Dawn on October 12 could have been resolved at a meeting of the Indus water commissioners, mandated by the Indus Waters Treaty to be held once a year. But the Indian assertion that these meetings will resume only once “an atmosphere free of terror is established” spells disaster for our farmers. The only safeguard that the Indus Waters Treaty offered Pakistan was through the Permanent Indus Commission whose meetings India has been routinely flouting under one pretext or the other. If the situation persists, Pakistan will have no option but to take the matter through the cumbersome route of World Bank and international arbitration. All through this period, India will enjoy undue exploitation of water resources at the expense of the people of Pakistan.

What can India not do?

Caught in nationalistic fervour, hawks in the Indian media have been blaming their previous governments for failing to exercise a water offensive like the one PM Modi is intent on implementing.

Indeed, India can hypothetically terminate the Indus Waters Treaty and restrict even the rivers flowing into Pakistan through the diversion of Indus rivers waters. But when it comes to practice, this position remains untenable.

The waters of the Indus rivers flow through deep gorges of the Karakoram and Himalayan mountains. The only way to divert water from here is to tunnel through hundreds of kilometres of the world’s highest and toughest mountains.

Granted that all technical problems have technical solutions. However such an undertaking would be financially prohibitive, technically extremely challenging, and with minimal cost-benefit ratios. The longest tunnel dug in the world is the Gotthard Base Tunnel to facilitate rail travel. Although it is being drilled for the last 22 years through the Swiss Alps, it is merely 57 kilometres long and has already incurred an estimated cost of 12 billion US dollars. For India to divert waters of the western Indus basin rivers for meaningful use, it will have to dig up to 300 kilometres of tunnels.

As such, diverting the water going into western rivers which feed Pakistan is not a feasible option.

In addition, India has remained part of the Non-Aligned Movement and prides itself in having contributed towards drafting many international conventions including the UN Convention on the Law of the Non-navigational Uses of International Watercourses 1997, Helsinki Rules 1966 and their Berlin Revisions of 2004. Politically, an attempt to scrap the Indus Waters Treaty would bring massive international condemnation to India.

India’s planned infrastructure projects: how can they affect Pakistan?

While India may not have the capacity to turn off the taps immediately or divert the waters of the rivers flowing into Pakistan, it is undertaking a number of projects that could have an adverse impact on Pakistan’s water availability in the future.

The Indus Waters Treaty handed Pakistan the right to unrestricted use of the three western rivers — Indus, Chenab and Jhelum. The eastern rivers — Sutlej, Beas and Ravi — went to India. While the treaty allowed India to divert the waters of the eastern rivers, it could only tap into 3.6 MAF of water from the western rivers for irrigation, transport and power generation.

Experts at the Indus River System Authority (IRSA) complain that India has been constructing huge water storages on all six Indus basin rivers, not just on the three under its full control. For example, Baglihar and Salal on Chenab are already generating 450 MW/h and 690 MW/h respectively while the planned Bursar and Pakal hydroelectric projects also on the Chenab will produce 1020MW and 1000 MW/h respectively. The size of the energy outputs is an indication of the size of the projects. Pakistan’s Mangla, for comparison, generates 1000MW/h.

In all, India is in different phases of planning or construction of some 60 storages of varying capacity over the six Indus rivers, though analysis of satellite imagery obtained by Dawn suggests the number may be more [see map]. Technical experts in Pakistan worry that such storages will provide India ultimate strategic leverage of increasing or decreasing river flows during tensions between the two countries, even if it cannot legally divert the waters for its own use.

Sheraz Memon, additional commissioner of the Indus Water Commission, argues that India does not have sufficient capacity to withhold the water of the western rivers nor it can divert them. “But they may keep the implementation of the treaty at a snail’s pace, for example through delaying the meetings of the Permanent Indus Commission and not providing data or information about their new hydroelectric plants,” he warns.

There is also talk of expediting the construction of the Pakal Dul, Sawalkot, and Bursar dams, also in Jammu and Kashmir. Indian media reports claim that the Indian government might also resume work on the Tulbul Navigational Project — also known as Wullar Barrage — work on which began in 1985 but stopped soon after Pakistan lodged a formal complaint against its construction. Pakistan opposed the project at the time since it would have allowed India to store, control and divert River Jhelum, which was a clear violation of the Indus Waters Treaty. If completed, Tulbul will adversely affect the water storage potential of Mangla Dam.

Original sins

During 1956, Pakistani negotiators were warned by their irrigation officials and technical experts not to accede to Indian delegation chief ND Gulhati’s demand — also supported by the World Bank — to allow India to build small storages over the western rivers.

Until the signing of the treaty, the Indian predicament was that while Customary International Law and conventions gave them a legitimate right over 33 MAF or 21 percent of the six Indus rivers water — corresponding to 21 per cent of the Indus basin being in Indian territory — India had little room to utilise this water within the basin. The Indus Waters Treaty gave them an opportunity to divert water towards Rajasthan for irrigating over 700,000 acres of land which was previously bare sand dunes.

Explore: Historical follies – Where Pakistan went wrong in negotiating the Indus Waters Treaty

Before the Treaty, the waters of the Ravi, Beas and Sutlej were utilised for the cultivation of lands as far south as Bahawalpur State. Suddenly there was no water for thousands of farmers on this side of the border until Tarbela Dam was finally opened in 1976.

But Pakistani negotiators at the time acquiesced, on the pretext that this shared water would also benefit their Muslim brethren in Kashmir. Pakistani negotiators did not even bother to specify the size of the so-called small storages but agreed to India officially withdrawing up to 3.6 MAF of water for local use. In comparison, the current storage capacity of Mangla Dam, after expansion, is about 7.4 MAF.

Given the pliancy of Pakistani negotiators at the time, the Indus Waters Treaty emerged as a treatise that was skewed in favour of India. Perhaps it is for this reason that PM Modi announced that while India will not review or abrogate the Indus Waters Treaty, it will exploit water under its share to the fullest. It will, for example, build more run-of-the-river hydropower projects on the western rivers and irrigate over 400,000 acres in Jammu and Kashmir.

One thing seems certain: India will continue to build additional storages on the Indus rivers to store more than its allowed quota of up to 3.6 MAF of water. This will also provide hawks the option of delaying khareef crops in Pakistan from time to time. If the winters’ torment is harsh, delay in summers sowing would be a national crisis.

Looking within: what Pakistan needs to do

There is a real danger that current Indian antics will push Pakistan towards construction of very large dams at Diamer and Kalabagh, displacing more people and adversely impacting our environment which is already in a poor state.

“India is employing pressure tactics on Pakistan by announcing it will speed up dam construction,” argues Dr Pervaiz Amir, director of the Pakistan Water Partnership. “Pakistan must address its own internal water security and create sufficient storage. India has 200 projects in hand. Saving water is a planned response by India, and Pakistan should follow suit.”

But increasing storage capacity is not the same as storage capacity from large dams, which in any case is not the panacea that it is made out to be.

During the last 69 years, Pakistan has developed three major water storages at Tarbela, Mangla and Chashma with a cumulative storage capacity of 12.1 MAF against average water flows of 133 MAF annually through the three Indus rivers. There have been little or no independent studies to either assess or address the issues of resettlement, the massive loss to the environment and overall economic cost due to construction of large dams. In addition, issues of climate change —which have only recently come to the fore — raise questions about the risks posed to and by large dams. Freak weather conditions, such as unusually intense cloudbursts, are becoming more common and have already resulted in threats to people living downstream of large dams.

To add insult to injury, we have been ruthlessly pumping out underground water through tubewells. Such pumping is severely affecting the underground water levels in the country and often being replaced by saline water, adversely affecting agricultural output. The number of tubewells in Pakistan has risen from 2,400 to over 600,000 since 1960.

While we could continue to curse the World Bank bureaucracy, American interests in the region and Indian cunning for having deprived the country of its water share, we must also look at our own wasteful attitudes towards utilisation of available water resources as well as the politics around available water.

Pakistan loses almost half of its existing available water through seepage in the irrigation system [see table]. This is a prime cause of waterlogging and salinity which are turning large areas of fertile land barren. Surely lining of water canals and water courses should be the first priority in saving the water we have at our disposal, rather than the construction of large dams.

According to WAPDA’s published figures, average cereal production in Pakistan against a metre cube of water is mere 0.13 kg. In India, the same amount of water yields 0.39 kg, yield in China is estimated at 0.82 kg, in the US 1.56 kg and in Canada 8.2 kg [see table]. Clearly better management of water resources, efficient crop yields and serious efforts towards population control will be much more advantageous than building additional dams and storages that will ultimately result in catastrophic environmental issues and human resettlement crises as being faced in India and China.

The issue of water supply does not simply concern the two nuclear-armed neighbours. Tahir Rasheed, CEO of the South Punjab Forest Company (SPFC) and a senior environmentalist, warns that if the Indo-Pak water crisis spirals out of control, the friction can engulf other countries of the region as well, especially Afghanistan.

Read more: Speech by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto on Riparian Rights in International Law

“Afghanistan is [currently] utilising 1.8 MAF of water [from the Kabul River which feeds into the Indus], which is estimated to rise to 3.6 MAF in the future,” says Rasheed. “Pakistan currently does not have any water sharing accord with its northwestern neighbor. But the projected increase of water use by Afghanistan can affect the lower riparian, Pakistan.”

In conclusion

The Indus Waters Commissioners of Pakistan and India have met every year since the Indus Waters Treaty came into force. The wars of 1965 and 1971, the Siachen and Kargil conflicts and the Mumbai attacks weren’t able to dent it. In standing the test of time, the treaty has shown that it generates the least conflict and more cooperation between the South Asian neighbours.

The chances of India scrapping the treaty altogether and diverting the western rivers are negligible to none. But one must not put past India its flouting the spirit of the treaty and manipulating water flows to turn the screws on Pakistan.

Pakistan’s response, however, should not be as cavalier as when it negotiated the treaty, ignoring sound technical advice and short-changing itself in the bargain. It needs to put its own house in order on an urgent basis — by better utilising its existing water resources. Pakistan’s protestations against India’s perfidy will then carry far more weight.

Fahim Zaman is a Dawn staffer.

Syed Muhammad Abubakar is an environmental journalist with an interest in climate change, deforestation, food security and sustainable development. He tweets @SyedMAbubakar.

Research and cartography (Dawn-GIS): Dr Nawaz Huda, Maliha Naz Rana, Khalid Hanif

Published in Dawn, Sunday Magazine, October 30th, 2016