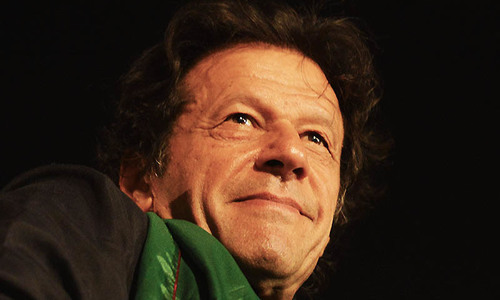

IMRAN Khan has sobered up a bit. The often wild diatribes aimed at all and sundry are now infrequent occurrences.

There’s a lot more attention given to some admirable reforms being carried out in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, such as in policing and the environment, and while there is still an inability to accept election results, the discussion of electoral malpractices and irregularities has taken a slightly more constructive tone. A few days back, there was even talk of forming a joint front with other opposition parties — led by the PPP — in the National Assembly.

Part of this may be due to circumstances — there was no finger raised during the dharna, local body election results haven’t been particularly favourable, and the sense is that the electorate isn’t actively unhappy with the current regime (though the ruling party shouldn’t mistake that for complete satisfaction either). Another factor may be the influence of several party leaders who’ve taken a greater role in managing the party’s public posturing, such as the infinitely more placid Chaudhry Sarwar.

In this context, the recent statements by the Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf chief on an alleged Nawaz Sharif-Narendra Modi secret meeting in Nepal, and the one-minute interaction on the sidelines of the Paris summit, come as a bit of a throwback to more rancid times. In a speech delivered to the media, and simultaneously serialised on Twitter, Khan accused Sharif of several wrongdoings.

The recent statements by the PTI chief on an alleged Sharif- Modi secret meeting in Nepal come as a bit of a throwback to more rancid times.

First was his decision to meet another head of government without taking parliament into confidence. The second was maintaining secrecy about the ruling party’s position on relations with India and on the subject of both meetings. The third, and this was vintage 2013, allowing his ‘private business interests’ to dictate his foreign policy decisions. The backdrop for this was the revelation by an Indian journalist that an Indian steel magnate had facilitated the secret, backchannel meeting between Sharif and Modi.

Sharif’s reluctance to engage with parliament on any number of issues is worthy of criticism. As leader of the house, he often forgets the primary responsibility entrusted to his party is via the legislature. However, the secrecy of both meeting Modi and the contents of their meeting is somewhat understandable.

Given the rabid rhetoric from the Bharatiya Janata Party, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and Shiv Sena bhakts across the border (whether its related to cricket, Islam, or Kashmir), tensions on the LoC, and the rise of anti-India sentiment amongst domestic religious groups, and in the right-wing media, open discussion on the issue is currently a no-go area for both governments.

The second accusation, of the prime minister cowering from being honest and bold about his views regarding India in public, is made from the comfort of being in distant opposition, and with the knowledge that it’s a way to garner cheap brownie points with a segment of the electorate.

Perceptions of backlash — whether empirically grounded or not — are crucial in shaping decisions taken by any leader. Nawaz may be more cautious than most, but he cannot be faulted for attempting to tread this particular ground lightly. Most observers and serious IR academics would agree that talking in secret is better than not talking in postured hostility.

Thirdly, the assertion that a secret backchannel meeting damages the credibility of the military is built on several faulty beliefs — the principal being that the military has to be consulted on all issues of foreign policy vis-à-vis India. Imran Khan’s opinion is that a brave, forceful civilian leader (naturally like himself) would be able to convince the establishment of his chosen path of action. Nawaz Sharif, according to him, is not that leader.

What he naively assumes in this instance is that the establishment would ever be willing to take dictation from a civilian leader – brave or otherwise — and that it wouldn’t actively redress any attempts at rebalancing power between the two on such issues. This naiveté is, presumably, a function of having spent zero time in government, and holding a particularly skewed reading of the history of inter-institutional conflict in Pakistan. Revealed preferences of the military in phases where leaders have attempted to be bold show a particularly different outcome.

Finally, the PTI’s stated position is that it wants peace in the region, driven by the economy, and based on mutual respect, and resolution of long-standing issues between the two countries. This is a noble position, but to hold it in isolation from the government’s efforts is counterproductive.

If the PTI has an independent, well-thought-out policy regarding India, it should throw up a road map in public. Any such plan, if it were smart enough, would then also have to account for domestic institutional imbalances, and the expected backlash. Otherwise keeping statements vague and imprecise, invoking honour and bravery, and bringing up the spectre of ‘private interests’ (with no clear proof) is at best empty politicking, and at worst strengthening the security-state orientation of the country’s foreign policy.

This past week, the PTI’s provincial body in Punjab released two white papers on the government’s mismanagement of the education and health sectors. A summary of these documents made it to the deep, dark inner pages of local Urdu newspapers, and a preliminary reading suggests they raise some very important points.

An opposition that wishes to be substantive and mature would devolve far greater time on such outputs; ones that may actually have a pervasive impact on the electorate. Perhaps for his next speech, the PTI chairperson would want to focus his energies on precise failings of the government in service delivery, rather than drumming up nationalist hysteria on a foreign policy issue. In time, if and when he comes into power, a switch of this nature may even make his own job a little easier.

The writer teaches politics at Lums.

Twitter: @umairjav

Published in Dawn, December 7th, 2015