Herald Exclusive on PTV: Cracking the code

|

This article was published in the Herald's January 2014 issue

By Salman Shahid

There was a time when there was only one channel,” said the man from Pakistan Television Network (PTV) and then went on to add with an expansive gesture, “And now there are about a hundred!”

“That brings me to the point,” I interjected, “How do you still maintain a different censor policy from the other channels — or you don’t?”

“You are right, we cannot afford to retain an exclusive policy; otherwise we lose on the revenue that comes from the advertisements,” the PTV man replied.

To imagine a Pakistan with multiple channels 30 years ago was as inconceivable as was the advent of the mobile phone.

That was a time when PTV ’s transmission started with Fehmul Quran (a programme on teaching the Quran to children) and closed with the national anthem at midnight, lasting about six hours in all. All this has changed since then and, with it, many of the elements of PTV ’s censor policy.

I learnt that the cardinal features of PTV ’s professed policy are to play custodians and guardians to state, religion and culture. Amongst the curious don’ts that were mentioned to me and stuck in my mind were that PTV did not run advertisements of a hospital —though, I pointed out, that PTV does air promos for educational institutions, where it seems to compromise policy for revenue.

It does not run an ad of a product named after a revered person, such as Jinnah, for instance.

What was not mentioned was PTV ’s prime crime of shamelessly touting every government’s claims, false or otherwise, even if this is unavoidable since it is the official mouthpiece of every government and used to suit its interests.

For private channels, however, money makes the policy — whether it is about which ad to run or about how to treat a sitting government.

It is probably useful to recall the charter on which the national channel was formed. It was the brainchild of Altaf Gauhar, a senior journalist turned bureaucrat and kingmaker, who gifted it to General Ayub Khan as a vehicle for what he thought would promote his continued governance.

That PTV cannot save a government when its fall is imminent – Khan’s or anyone else’s – has been proven by time. Many a private channel nowadays would happily be on the other side of the barricades, trying to bring down a sitting government and patting itself on the back if and when it does fall.

My personal experience with ‘PTV morality’ happened when I used to make the occasional television commercial. I made one for a shampoo which died its death many moons ago. In the ad, a woman bounced a multicoloured ball.

The intention was to highlight the body and bounce in the woman’s hair and I thought we managed to illustrate this effectively by using this visual metaphor.

The catch we missed in the ad was what the censor man in PTV’s sales department caught. He brought to my notice that not only was the ball bouncing but certain parts of the model’s body were also complementing her efforts. I protested that there is no way of preventing that but there was also no way of convincing him to the contrary.

The production team was left with no option but to commiserate, in heathen fashion, the loss of the commercial and dump the 30-feet strip of film to the anonymity of a waste-paper basket. What rankled, however, was what the man in the sales department said as I was leaving the premises.

He told me to specifically convey to the model I had used in the ad that it was he who was responsible for shooting the commercial down.

This meant that the salesman was settling a personal score with that woman, at the expense of our efforts. Like anywhere else, those who have authority will at times misuse it. And, when a code is not too well defined, someone or the other is likely to use it to suit his whims.

The PTV man I was talking to disclosed, “The PTV censor code is a brief guideline with no really hard and fast rules.”

This means that any person given the authority in PTV can interpret that brief and expand on it according to his own conditioning and prejudices.

In contrast, private television does not have even so much as the pretence of a code; everything goes as long as the holy cows of religion and the ideology of the state are not under direct attack. However, religion is a not a commodity on PTV; more a whiplash to beat the errant and the sinful with.

For private television channels, on the other hand, both religion and morality are fast becoming essential ingredients in an entertainment diet that is readily gobbled up by the starving audiences.

There is also a censor board at PTV, comprising several people from various walks of life. At a particular viewing, at least four members have to be present. Two of them are usually from the channel itself.

As mentioned earlier, they are in the censor board as the custodians of religion, state and culture. But since the censor policy is broadly and loosely defined and left to individual interpretation, in truth, these custodians, more than anything else, are safeguarding their jobs while taking any decision.

This has, in effect, worked in favour of government after government. Fear of endangering jobs has made the PTV censor even more restrictive than the code had foreseen. Instances of this abound in PTV history and, not surprisingly, are best illustrated from General Ziaul Haq’s era.

|

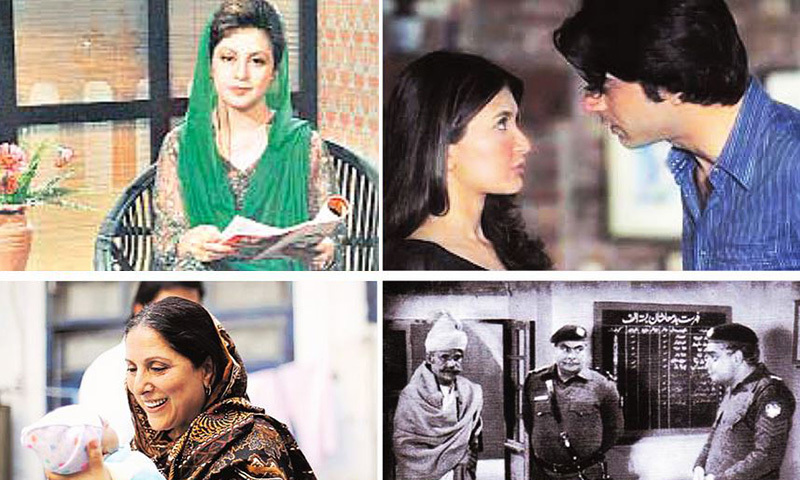

At the time, it was compulsory for women, newscasters, talk show hosts and actresses alike, to always don a dupatta over their heads.

In the case of actresses, a dupatta was compulsory no matter what the situation. So it happened that in a play, a woman was shown to have drowned and when her body was retrieved, her head was seen not to have shed its symbol of modesty.

Quite often, one would wonder whose interests PTV was guarding.

I was the protagonist in a serial from Karachi. It was called Seerhian and showed the rise of an ambitious young man, climbing up the ladder of success. The means he used to achieve his ends were often foul.

The serial was, eventually, supposed to conclude with him reaching the pinnacle of success as a politician and addressing a mass rally with the words, “Brothers, sisters and fellow countrymen.” The programme director swiftly flew in from Islamabad and had the ending changed. It finally concluded with me, as the politician, opening a door on a surrealistic, desert landscape and repentantly walking across its wastes.

Mind you, this was the year before Haq’s demise. So, why was so much effort put not to show a politician in poor light? After all, are we not all too familiar with seeing politicians and army generals as arch foes, happy at highlighting each other’s follies? Or does PTV shield the strong, regardless?

That PTV is more lenient to the high and mighty is illustrated most glaringly in its representation of the police. It is usually the pedestrian policeman or constable who comes for a grilling, while his superiors seldom receive similar treatment. Rarely will you see an officer taking a bribe or involved in any other offence.

This aspect of the national channel was very evident in Younis Javed’s popular series Andhera Ujala, which was telecast some time in the mid-1980s. While the lower cadres were often shown up to various misdemeanors, the police officer pontificated on moral uprightness and other goodness that man can rise to.

For private television, though, entertainment is mostly either about the life of the high and mighty or the intrigues and intricacies of the love lives of the urban middle classes. Social commentary at private channels, too, has become more focused on psychological and emotional subjects rather than economic and political ones.

Well-known television playwright and columnist Munnu Bhai recounts that in his 1984 serial, Abbabeel, he was held back from showing a Christian woman as a charitable and kind-hearted person and, instead, was told to depict the same character as a Muslim.

|

According to the PTV man I was talking to, this could not be all true. “Personal prejudice aside, we see to it that nothing repugnant to any faith, caste or creed is shown in our transmission”.

That might very well be the case but the occasional and latent bias that we have towards non-Muslim Pakistanis would surely find its way to the hearts of those who conduct affairs on our channels, including PTV.

The state broadcaster, however, is vindicated by what actor Shamim Hilaly tells me. She declares that she never found reason to decline a role on a PTV drama because of any discriminatory element towards non-Muslim Pakistanis whereas in the case of private channels she had to do that since they seem insensitive in their depiction of them.

Today PTV, like other channels, buys, rather than produces, a lot of its software (that is, programmes); so, it is not in a position to enforce its code right at the inception of a concept. Also, the stiff competition that other channels pose has made PTV relax its policy. In the era of no one channel monopolising the airwaves, the good, the bad and the ugly coexist and compete for attention — unlike in the PTV-only years, when sometimes even a single individual would decide what could be shown and what must be held back.

The Herald asked Muneeza Hashmi who has held senior positions at Pakistan Television Network (PTV), renowned actor for television and theatre Sania Saeed, playwright and teacher of drama studies Asghar Nadeem Syed and veteran actor and director Sahira Kazmi to discuss the state of Pakistani entertainment channels

|

Muneeza Hashmi

To the extent that I know, I would say that there has not been a diversification of themes. Turkish and Indian dramas have taken over; so, there is little incentive to innovate around local shows.

Sania Saeed

There is much more that television can talk about. There are so many big stories out there but somehow we are still stuck inside the four walls and the family dynamics, therein. The shows are all focused on the internal world, as if the outside world does not exist, even though we can’t but be affected by what is around us. So, it is not very realistic to do so, is it?

The drama serial Numm covers issues relating to the relationship of men and women; [another drama serial] Darmian portrays a working woman but again, inside the four walls of her house where the same old rules apply. In Aseer Zadi, we see patriarchy making women believe they have certain powers, which they, in fact, do not.

Asghar Nadeem Syed

Entertainment has not exactly diversified in terms of themes. It is a continuity of the previous year’s popular trends, mixed with foreign plays.

Popular themes which were followed by every television channel included the plight of women in terms of extramarital relationships facing emotional stress in the setting of domestic intrigues; shallow archetypes of romance and the so-called upper-class glamour, presented without any thought and meaningful content; and bad-taste comedy sitcoms and plays, designed to attract middle-class women.

Foreign serials, such as Mera Sultan and Friha, also dominated the scene.

Sahira Kazmi

Thematically, television has not diversified as much as it should have. Dramas continue with taking up the same themes, and soaps continue to be largely anti-women. The same can be said of morning shows. Each channel is copying the other, with the result that, with 80 to 90 channels on offer, there is very little variety. We mustn’t forget that Pakistan is a third world, developing country, and the middle class (the ones who watch television the most and who television entertainment caters to) is not terribly educated. So, television should be a means to get important issues across, not through intellectual stuff but through engaging storylines. And since there is no censorship as there was in my time, there is no reason not to do so.

|

Muneeza Hasmi

I don’t know about the laudable but perhaps the most despicable would be the import of Turkish plays. It is ludicrous to see women with green eyes and long, beautiful hair in short skirts speaking Urdu, of all things. The influx of Turkish soaps speaks volumes about our own dramas’ inability to entertain us.

Sania Saeed

Pakistani television actors are just phenomenal and they do a great job within confining and repetitive scripts. The writers are capable of composing better stories. The fault for the state of affairs lies with the channels that don’t make enough effort and undermine the viewer. Channels make the erroneous assumption that the audience is the middle-class housewife. Even if this were true, why do they assume that she is unintelligent? Usually, shows are about women confined to the four walls and don’t mirror the progress that women have made since the 1980s.

Asghar Nadeem Syed

If it is laudable to sell religious sentiment in the holy month of Ramzan and emotionally exploit the viewers’ faith, then television certainly did well. The most despicable feature was morning shows, hosted by female anchorpersons discussing artificial themes.

Sahira Kazmi

What is laudable, and should continue, is that a lot of channels are remembering our artists and people from the world of arts, culture and politics who have passed away, for example, remembering Noor Jehan on her birth anniversary. This is important because it is a way for younger generations to connect with our culture and heritage. I would request PTV to do more of that since it is the channel with the most archival footage. Conversely, I don’t see any improvement as far as content is concerned. Morning shows have also worsened this year, concerning themselves with mindless topics. I don’t think the ratings race can be used as an excuse for the state of television — if someone wants to do something different, they should do so and promote it aggressively because there is an appetite for something better. This demand is just not being fulfilled because channels aren’t doing enough.

|

|

Muneeza Hashmi

Watching television today is an utter waste of time. Television should affect minds; it should give audiences something to talk about; something to debate, but television entertainment is mindless.

Asghar Nadeem Syed

Political shows, in 2013, were mostly loud and controversial in terms of content and in terms of pushing the boundaries of sensitivity. Reality shows and dramas remained popular genres.

Sahira Kazmi

I don’t think any shows have been controversial or pushed boundaries this year. Soaps dominated the airwaves.